A variation on a theme

I received a blog enquiry asking if I could make a fire grate for a Silvercrest 5″ BR Class 4. The owner had inherited the locomotive but it was missing the fire grate. Given the age of the model Silvercrest were unable to help. I gamely said I would ‘have a go’ but on the basis of making a rosebud rather than a conventional bar grate.

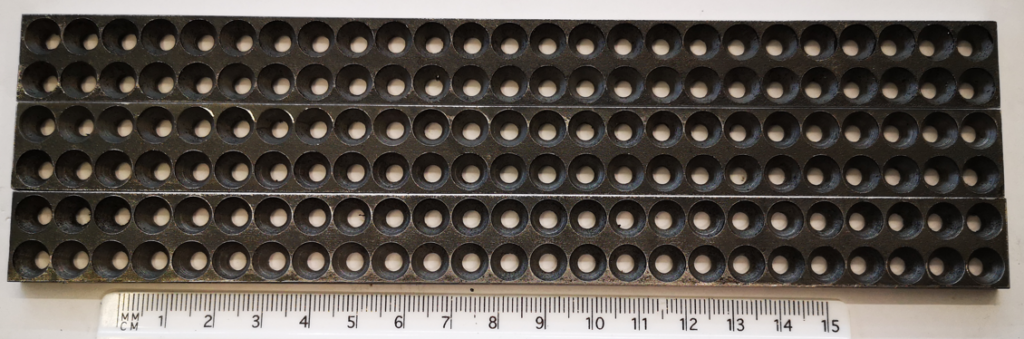

What I didn’t realise was that the grate on this model is made up of 3 separate long sections which are shuffled into place via the firebox door …

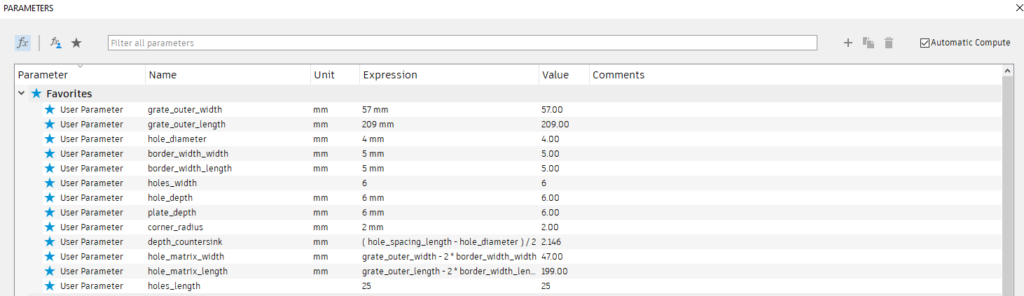

I asked the owner to first of all make a template of the grate size based on three equally wide sections of hardboard. This resulted in an overall grate size of 57mm x 209mm. From this I used my Excel spreadsheet to derive a grate with 15% hole area occupancy from a matrix of 25 x 6 holes each of 4mm diameter counterbored with a BS4 centre drill.

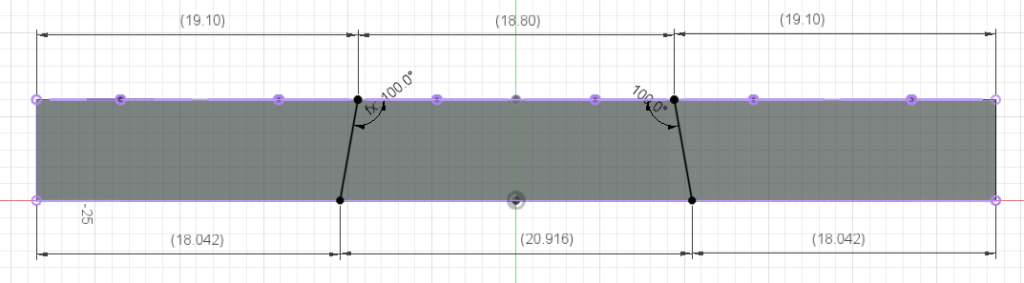

I thought it might be a good idea to have a draft angle on the inner edges of the grates. Don’t ask my why – it just seemed like it would make it easier when dropping the middle section into place and perhaps reduce air leakage through the joint .. and of course this makes the design more complicated than necessary and added to my machining woes. This can be seen on the image above.

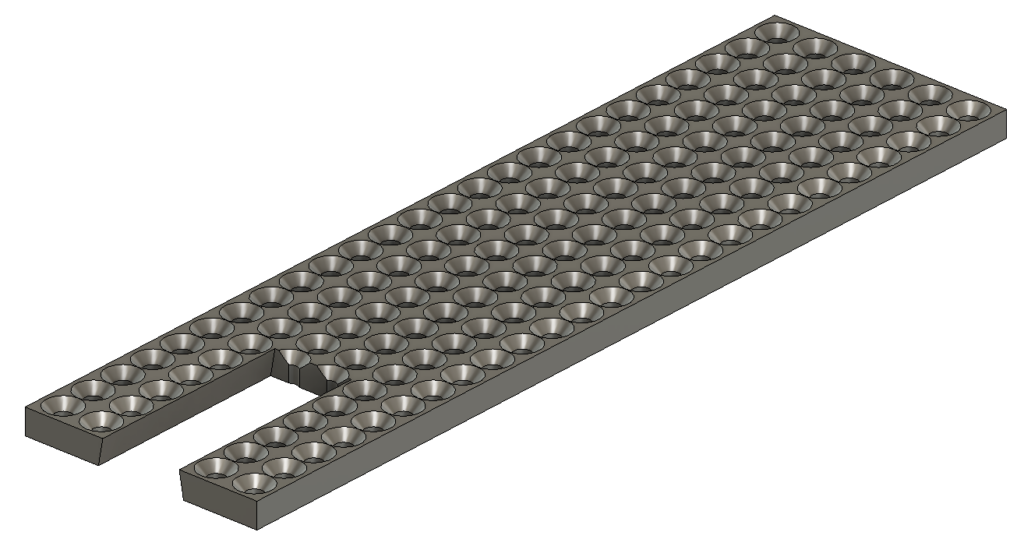

The design was created as a single grate and then extrude cut into the three sections so the middle and outside grates could have their own CAM program. Here is the Fusion model view looking from the under side.

Having grasped the basis of the design I sent the owner a set of 3D printed grate sections which he cross checked and confirmed would fit correctly. (Could these be the ultimate chocolate fireguard I wonder ?)

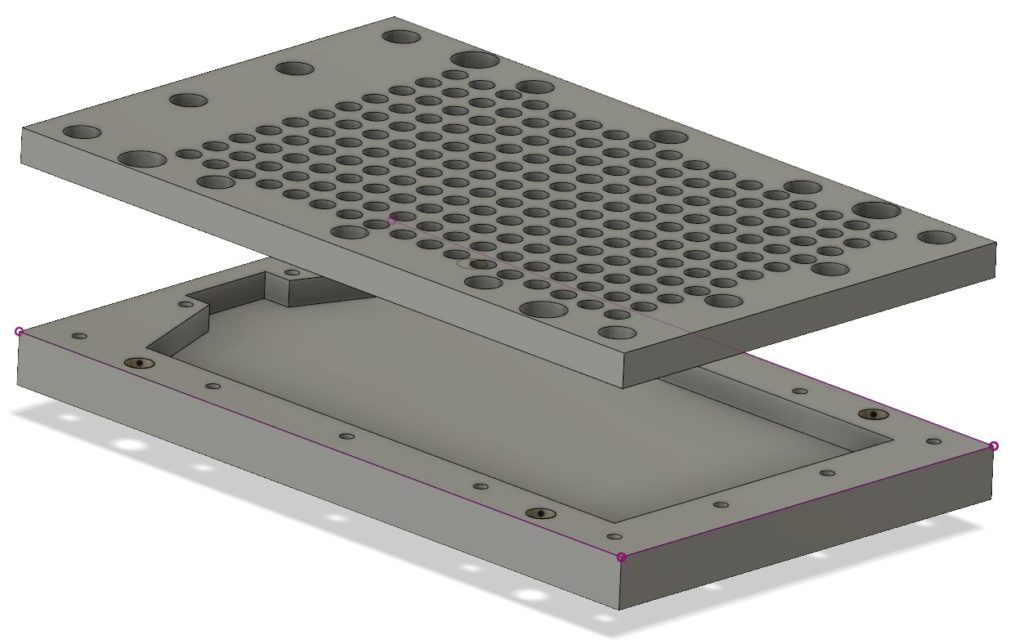

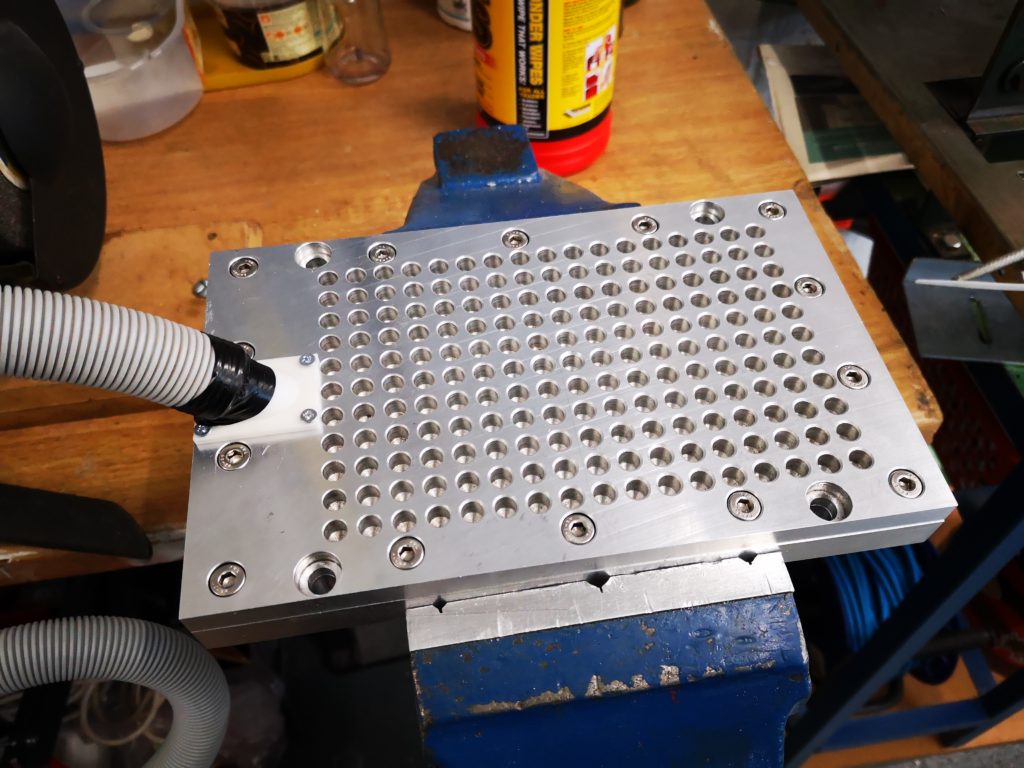

The next step was to think about the CNC CAM operations and the stock holding. I find holding the stock and the order of doing things to be the most challenging part of the machining process. As the three sections of grate were all under 25mm I opted to use 6mm x 25mm BMS as the base stock material. I had the Fusion 360 model reference the stock at the centre point. This is easy to probe using the Tormach PathPilot inbuilt routines. I cut three pieces of the BMS to 215 mm lengths and mounted each in turn on parallels in the machine vice. I had a vice stop set up to make the process repeatable. Each section was then drilled for the 4mm through holes (50 off in each) and then counter bored with the BS4 centre drill such that the taper on the drill finished flush with the stock top. This just left the outer profile of the model to be cut on the residual stock.

This was accomplished by using a piece of 30mm wide BMS as the sacrificial backing jig mounted on parallels. This was centre referenced and a number of the 4mm hole locations were drilled at 3.2mm and then tapped 4mm. These holes were then used to bolt down the three grates in turn so they could be profiled to size. The profiled width had to be the maximum width ignoring the intended draft profile (i.e. 19.10mm + 20.916mm). Here is the end view (upside down) showing the three grates with their draft angle .

The machining process was then transferred to my Myford VMB manual mill. This was set up with a tilting vice set to 10 degrees. The two bright edges of the centre grate and one edge of each of the outside grates were then blackened with a Sharpie before each being placed in the tilted vice and skimmed at 10 degrees such as to just remove the blackened surface.

The resulting grates all butted up together nicely and the job was complete. Here is the bottom side view.

These were shipped off to the owner for trials and he later confirmed that they fitted nicely into the firebox. I am not sure if anyone has made a rosebud for a Silvercrest with split grates so it should be interesting to see how well this configuration steams out on the track.

I think the above should give you enough to think about but there is one other spin off that resulted. While drawing up the grate in Fusion 360 I decided it would be much more convenient if the rosebud grate design could be automated using Fusion’s parametric functionality.

This resulted in the Excel spreadsheet being modified and the Fusion model also being updated. The result is the ability to get all the factors needed for the Fusion parameters from the Excel sheet (but you have to manually copy them between Excel and Fusion).

Here is a ZIP file with both these files included.

Update : the user has reported back that the grate performs well. Like other installations of a Rosebud grate, he has found a need to keep the blower slightly open.

Links to similar or related post are listed below : –

- Swiss Vapeur Parc Festival Week

- 3D Printed Jigs to the rescue

- Rosebud Fire Grate on a Silvercrest BR Class 4

- Simple Water Level Sensor for Live Steam Locos

- French Model Steam Engine Gathering

- Replacement Whistle on Polly V Steam Engine

- Bad day steaming with my 5″ Polly V live steam locomotive

- Lempor Nozzle added to Poly V 5″ steam locomotive

- Setting up the timing on a Polly V locomotive

- Halloween Steaming of the Polly